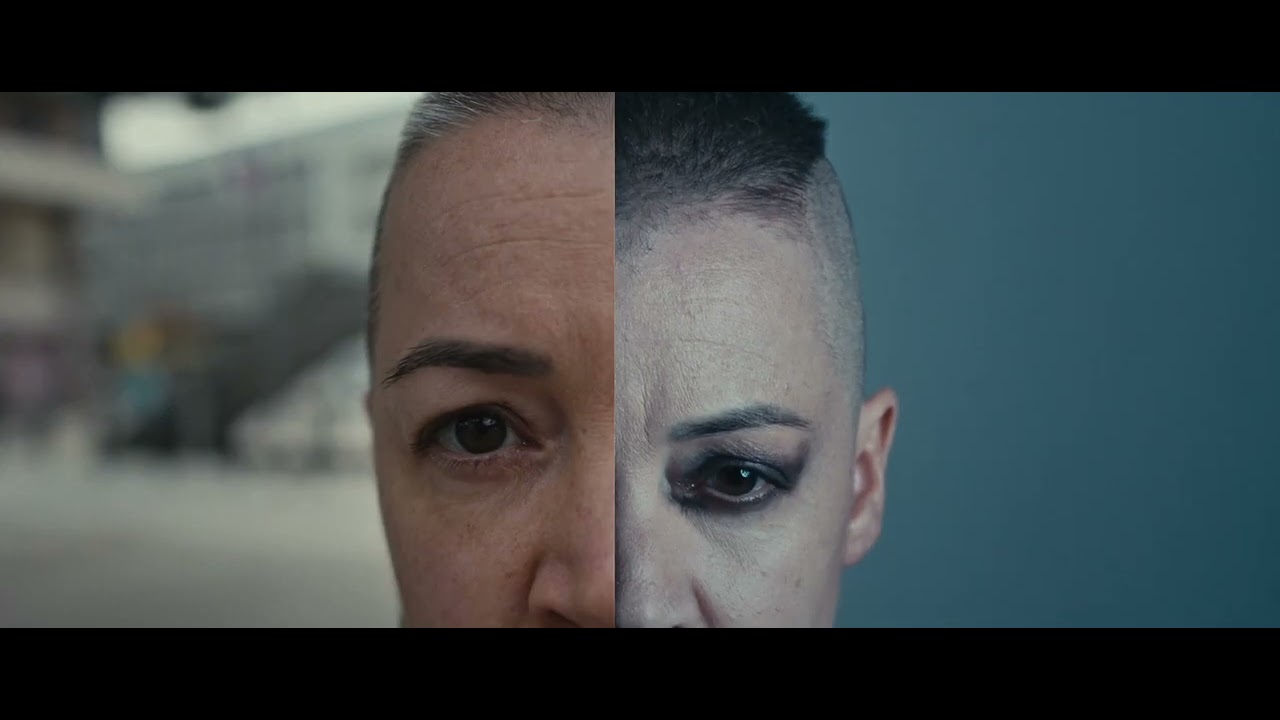

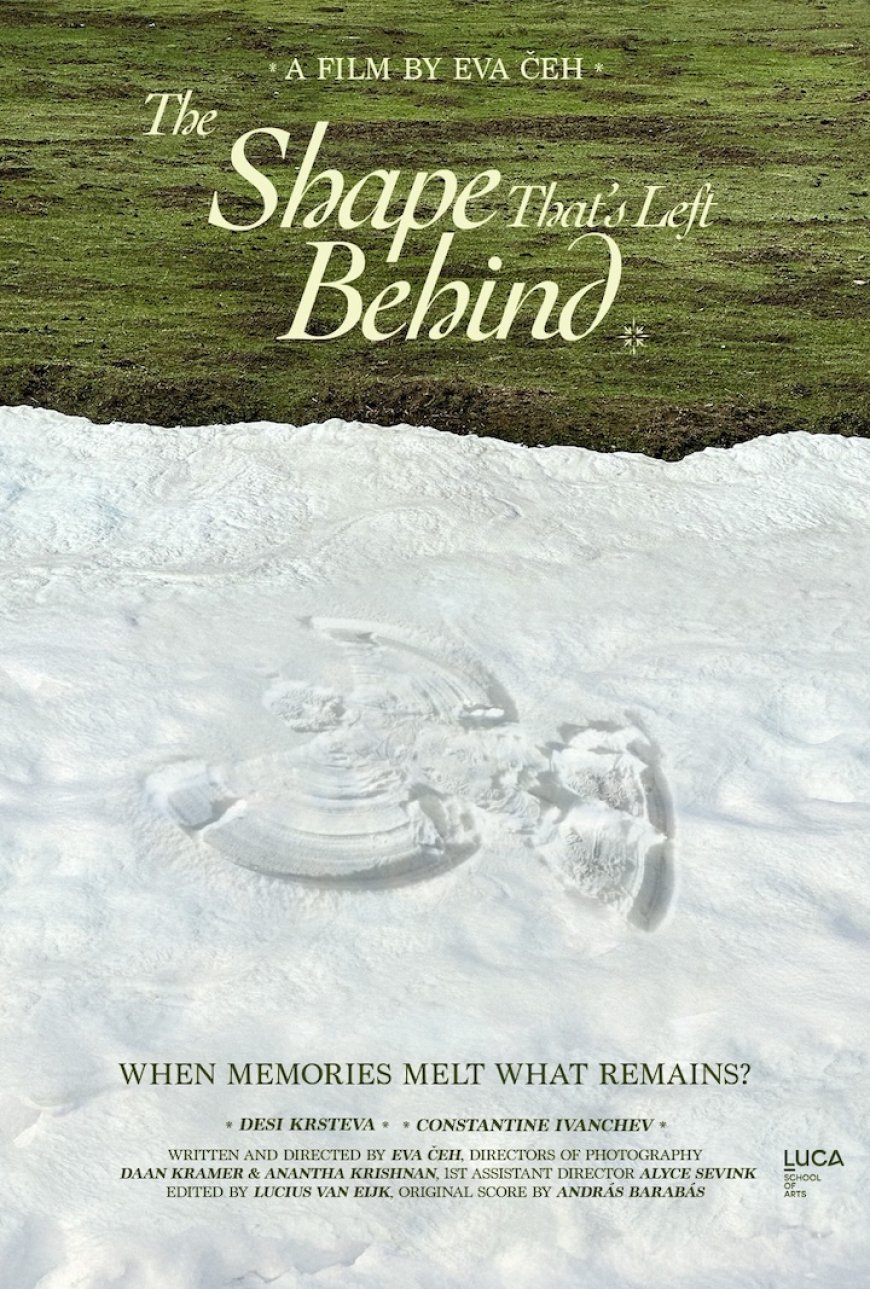

The Shape that's Left Behind: Let's talk about environment with Eva Che

In this interview, Eva Ceh, director of the short film The Shape that's Left Behind, takes us through the behind-the-scenes of her film and shares her environment and filmmaking tips. This interview is a part of our "Films for a Change 2025" collection: short films sparking social change online.

Eva, can you tell us more about yourself and your short film The Shape That's Left Behind?

Hi, thank you for this invitation and for the space to present my first short fiction film, a climate fiction. A word on me: I am a filmmaker based in Brussels and a graduate of the MA in Film at LUCA School of Arts. This film was my graduation project at LUCA, and I worked on it for two years. Originally, I come from Slovenia, and since my university studies I have been living abroad in several countries across Europe and Latin America. With an interdisciplinary academic and professional background in the social and political field, I like to challenge myself by merging creativity with social and environmental themes. Like many filmmakers with such a background, I first entered the world of film through documentary, which offers many opportunities to explore stories that reveal how our lives are woven into the larger fabric of the world. This is also where the idea behind The Shape That’s Left Behind began. It interweaves grief and a mother–son relationship with the wider reality of climate change. For me, climate change is not only a planetary crisis but also a deeply personal one, which I was keen to explore through film.

What was your inspiration for sparking discussion around this topic? How would you say your short film explores or suggests a change?

My climate change awareness journey started about a decade ago, and since then I have moved through different phases, from denial to anger, grief, etc., and eventually towards finding some sense of meaning, including through making this film. Wanting to contribute to positive change, I studied these issues at university and later worked on sustainability and climate related topics, so I have been gaining knowledge and reflecting on this for quite some time. I was already motivated to engage with this monumental challenge through film and to see what it brings. My graduation film just had to be about climate change in one way or another.

Climate change is often presented as something so vast and distant that it is hard to imagine it as an intimate experience. The challenge of climate narratives is to bring it closer to people and their daily lives, to make it relatable. Yet, in one way or another, even living in privileged parts of the world, I believe we have all experienced climate change to some degree. If not through major events like flooding and heatwaves, it is present in subtler ways. For instance, the cherry tree in my parents’ garden kept blooming too early in spring and then freezing. While we could always count on cherries from this tree for decades, suddenly this was gone.

It really does take a village to tell a climate story. Climate narratives are emerging as a new genre, widely discussed by storytellers, scriptwriters and filmmakers. Green production is advancing with plant-based catering, fewer flights and the sharing economy, but there is still room to innovate in WHAT and HOW we tell climate stories. There is so much left to invent, and being part of this wave of filmmakers and collaborations excites me and drives my own call to action.

A word on this WHAT and HOW: The research behind the film draws on my own experiences, as well as exchanges with communities and practitioners working in climate psychology, imagination activism, civil society and climate science. The film was shaped through engagement with emerging climate narrative spaces, including the first edition of the Changing Climate Narratives course by Climate Spring in collaboration with TorinoFilmLab, and the first Beyond Tragedy gathering. It also brings together insights from climate psychology, particularly Caroline Hickman’s climate change emotional transition curve, future thinking approaches such as Rob Hopkins’, and ideas from Hospicing Modernity by Vanessa Machado de Oliveira The way we live is reflected in the way we tell stories and make films. Our values, the aesthetics of a film, its narrative structure, all of these transmit meaning. Just as many aspects of our lives have

changed, or should change, so that future generations can have a future, the way we make films should

also evolve. Every decision in filmmaking can be reflected on. From the values characters hold and their desires, are they longing for nature or a walk in the forest, to lifestyle choices, do they drink tap water or a canned soft drink at dinner, do they ride a bike, to the aesthetics of the film, such as normalising second-hand objects or mismatched furniture rather than perfection. Having dived deeply into climate narratives, there were many considerations to take into account in order to do justice to the topic. One of them was staying away from utopias and dystopias, which also

means avoiding the absolutes of all good or all bad that rarely reflect real life. Our lives are much more

complex, and audiences tend to appreciate that complexity. My main reason for keeping the story

grounded and realistic was to bring it closer to people, in the hope that they could recognise themselves

in the position of the main character.

Another important consideration was avoiding tokenism, such as presenting symbolic actions like using

a reusable straw as solutions. This is a tricky area, because on the one hand every action, big or small, does matter. However, responsibility should not be placed solely on individuals. It is well known that most emissions are caused by a small number of fossil fuel companies and focusing too much on individual responsibility risks letting the biggest polluters off the hook. I was also interested in questioning dominant story structures in mainstream cinema, which often follow a plug-and-play model with a strong focus on future turning points. We are willing to sit through an entire film expecting something will happen at the end. This can be problematic, as it takes attention away from the present moment and leaves it largely unexplored. A similar problematic pattern exists in political narratives around climate change, where action is postponed to some distant future, in 2030 or 2050, rather than now. Yet climate action can no longer be deferred. The future is already here, and our stories need to reflect that by paying more attention to the present moment.

These are just a few examples of cinematic tools that need reassessment, but there is much more to consider. I would be happy to expand on this on another occasion. For this film, I found that emotions, and the way we experience the world through both our feelings and our bodies, offer a powerful way to explore the present. This led me to focus on how grief could be translated into cinematic language, particularly through the structure of the story.

Finally, the making of this film sparked many meaningful conversations and raised awareness about climate change among the cast and crew, as well as at LUCA. Like myself, many people involved in the film were already seeking ways to engage with climate action, and the process created a shared space for reflection and exchange.

What was the biggest challenge you faced on the production of The Shape That's Left Behind? How did you overcome it?

Considering the story is set in Brussels during a hot Christmas, this meant we had to film across both winter and summer. It was challenging to keep the cast and crew available over a long period and to coordinate everyone’s availability. Often, we had to find replacements. There were also the classic challenges of making a student film with very limited resources, relying largely on people’s goodwill. Everyone involved needed to find their own reasons to collaborate on the project. For some, it was friendship; for classmates, mutual support on each other’s films; and for

others, very importantly, the desire to contribute to a project aligned with their values, including climate change. The dedication and talent of several key people were crucial in elevating the quality of the film

and seeing it through to the end. Above all, it was about continuing step by step, without getting overwhelmed by everything that needed to be done for the film to be completed. And grit. Just keeping on going. Seeing the film finished is already a major achievement. I am very proud of what we have made and grateful that we have reached this point. Sharing it with the cast, crew, friends and my wider network has been rewarding, especially seeing their first reactions.

Tricky question, but one that sparks discussion among us artists: why do you create? What is your motive, and what pushes you to explore topics such as social change?

Cinema is magic. It is an art form and a craft with endless possibilities of themes and perspectives to

explore, and that is what I love about it. Intellectually, it is a playground that feels almost impossible to

exhaust, always opening up new adventures and stories. Filmmaking is also a deeply social activity. You

depend on others at every stage, which makes the process complex but also deeply rewarding. It creates

connection with people and allows for a deeper exploration of our lives, our relationships with one

another, and with the world around us. The impact part feels almost automatic for me. I am drawn to questions such as what people care about, what drives and challenges individuals and communities. Filmmaking allows me to engage in

conversations about reality and the state of the world, and sometimes it creates a strong urge to do more, to take action. I find it difficult to ignore the condition of the world we live in my practice.

A lot of people on indie-clips.com are independent and/or beginning filmmakers. Can you share one piece of advice to our audience of independent filmmakers making their first short film?

It takes a lot to make films. It requires resources, or privilege if you will, such as the ability to invest a

considerable amount of time, having a network or community to make the film with you, and having the

peace of mind to be creative in the first place. Starting on a small scale, embracing limitations and focusing on what truly matters is essential. No big production or budget can compensate for a good story or interesting characters. If the film tells what you want to tell, that is what matters. Feed your mind and go out into the world to research your story. It is rare to make something meaningful in isolation. Finding a community, whether a writing group, peers or an interest group, can help you move forward in the process and keep you accountable to yourself.

Any future plans? Tell us more about your upcoming projects!

Yes. Like many emerging filmmakers, I would like to develop a feature film and to collaborate on a larger project, working with producers and people I can learn from and grow with in my filmmaking practice. I keep folders where I collect ideas over the years. I casually journal, observe everyday moments and note down reflections around topics that interest me. Occasionally, one of these ideas deepens and becomes the starting point for more focused research and development.

At the moment, I am developing two such projects further. The first idea is very local and Brussels story. It is a docu-fiction I have started researching around street artist performers in Brussels. The second centres on Andean hip hop. During my first Master’s degree, I wrote a thesis on Quechua rap and began a collaboration with a Peruvian rapper that grew into a lasting friendship. Over the past decade, we have often spoken about developing a film together. Now, having completed my degree in film, we are actively looking for opportunities to expand on this idea.

Where can we see your work? Any way our fellow filmmakers can get in contact with you?

Webpage: https://evaceh.com/

Email: Evaceh.film@gmail.com

Ig: https://www.instagram.com/eva_ceh/

The film’s Ig account: https://www.instagram.com/shapeleftbehindfilm/

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0